Reflections from Ruth Harvey

A ferry port; a crowded boat with excited day trippers and holiday makers; white sandy beaches and blue-turquoise sea. So far, so familiar. The island of Wadjemup (known also as Rottnest Island) lies a 30-minute boat ride from Boorloo/Perth, on Noongar Country, Western Australia, in the Indian Ocean.

This island, inhabited by many hundreds of Quokkas (small marsupials mistaken as rats by the first Dutch sailors to land here in C16, hence the name Rottnest or rats nest in Dutch), was also the destination of around 4,000 Aboriginal men and boys incarcerated here until 1930 in the purpose-built prison, for minor offences. Many were held in dark dungeon-like rooms, 10 at a time, with capacity for no more than 4. Around 400 of these men and boys died in custody, some while trying to escape. Their burial site was for a while a camping ground.

We were welcomed ‘to Country’ by Uncle Neville Collard, Noongar Elder and guide, who led us in a ‘smoking ceremony’ where we were bathed and cleansed in the smoke of the fire, then invited to offer thanksgiving to all of Creation by throwing sand into the sea.

The generous, open-hearted welcome of Uncle Neville onto land inhabited by his ancestors over millennia stood in stark contrast to the hostility of more recent settlers/invaders/colonisers. I was struck by Uncle Neville’s comment, after what was a deeply spiritual welcome, that ‘we don’t have religion – we have culture and law, or lore.’ In what he offered there was a deep sense of what I would understand as the fullness, or sacramentality of all: an integration of ritual and welcome; story-sharing and campaigning for justice; honouring of past elders while pointing to hope in present and future leaders – all of this and more was the sum of the wholeness of Creation.

The juxtaposition of the holiday camp, where until the 1980s a luxury tourist bunk could be booked in The Quad (Prison), with the horror of the chain-gangs and the chilling dungeons depicted in the island museum was deeply distressing.

We sat, once Uncle Neville had left, in the small chapel, considering his gift of welcome. We held stillness. We shared impressions and tears; anger at the hypocrisies of history; horror at the knowledge of ongoing injustices: “nationally it’s twice as likely for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men to be in prison than in university.” (changetherecord.org.au)

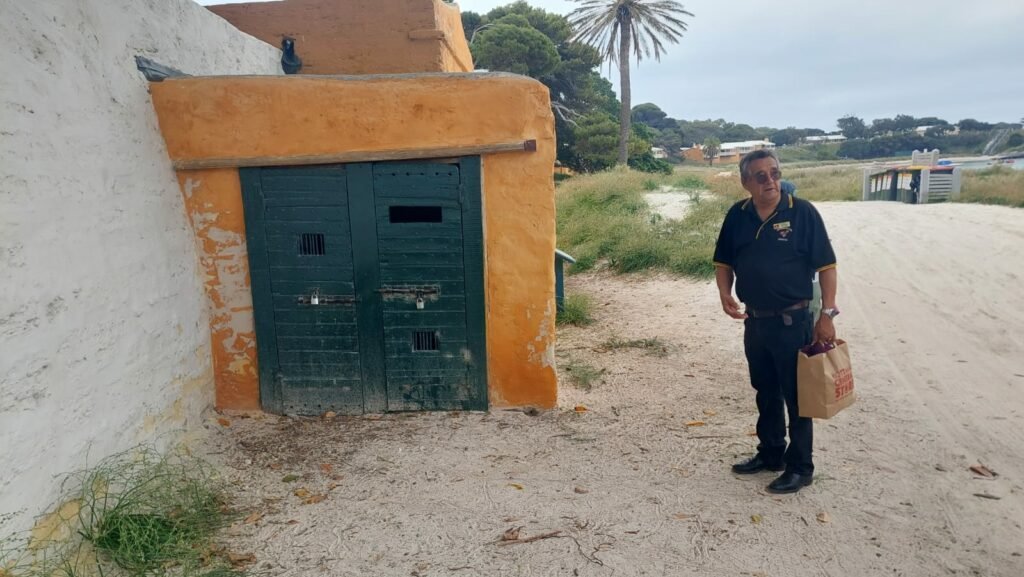

Uncle Neville

Back on dry land, we met the next day at Mooro Katta/Kings Park for a time of yarning and singing on Country. The generous open-hearted ‘welcome to Country’ offered by Della Morrison and Brooke Prentis, indigenous Aboriginal women, is becoming a familiar ritual of the peoples of these lands. We sang together with the ‘Madjitil Moorna’ choir, who through song offer ‘learning, healing, bringing cultures together.’ We drank tea and ate cakes and scones prepared by a local indigenous community. We swapped stories of faith and care for Creation.

If day one was a day of opening our hearts to the pain of the past, day two was a moment of healing amongst friends and strangers.

The backdrop to our yarning and singing circle was a mural of a tree prepared by Lisa Wriley, co-leader of the Wellspring Community. Each of us was invited to share, on a cloth leaf, examples of how we care for Creation, to be pinned to the tree as signs of hope. We were then invited to write in a book about why we care for Creation. These will in due course be written into the trunk of our tree-mural. And so as we journey across these lands, we hope that through sharing time and space with one another, we will continue to weave a pattern of understanding and inspiration in our care for Creation.

Reflections from Lisa Wriley

Yesterday we were on Wadjemup (Rottnest Island) with Nyungar elder Neville Collard. It was a rich time learning the history of the area, even back to 7000 years ago (the cool time) when sea levels were much lower and people could access several local islands via a land bridge.

The painful stories of the prison for Aboriginal men and boys (1838-1930), the first Aboriginal deaths in custody (nearly 400 of the 4000 people brought here never left). Many also died while being walked here overland in chains. The loss to their communities of these senior law/ lore men, fathers, uncles, sons and brothers was devastating. We saw the burial ground, now planted with trees that Neville wants removed to make what he feels is a proper memorial.

We saw the locked and empty Quod where the men were confined when not doing the hard labour mining salt on the island. This building until recently was used as holiday accommodation. Hard to believe the lack of regard for the history of this place.

The museum had some powerful stories, selected artefacts and videos of the Wadjemup Aboriginal Reference Group that seemed out of order, being at the back of the space. The description of the buildings and development of tourism seemed too prominent to me.

The time sharing with fellow pilgrims in the chapel was rich. There were 12 of us from a range of places from east coast and west coast. We were united in our gratitude to Uncle Neville Collard.

Mooro Katta Gathering

Photo credits: Nick Austin and Brooke Prentis